Tuareg Culture

Skip to main content

Search This Blog

Celebrating our African historical personalities,discoveries, achievements and eras as proud people with rich culture, traditions and enlightenment spanning many years.

- Get link

- Google+

- Other Apps

TUAREG PEOPLE: AFRICA`S BLUE PEOPLE OF THE DESERT

The Tuareg (Twareg or Touareg; endonym Imuhagh) are group of largely matrilineal semi-nomadic, pastoralist people of Berber extraction residing in the Saharan interior of North-Western Africa. The Tuaregs who are mostly Sunni Muslims descended from the Berber ("Amazigh branch") ancestors who lived in North Africa many years ago. Migdalovitz (1989) aver that "Garamante is believed to be the origin of Tuaregs and it was the predominant tribe in the south west of Libya some time before 1000 BC."

![]()

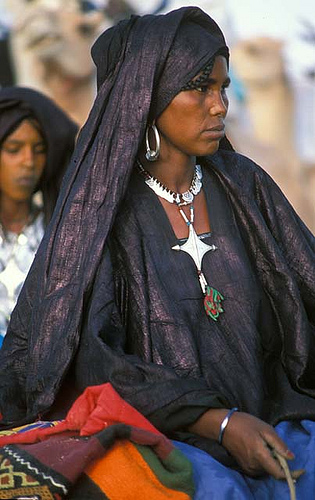

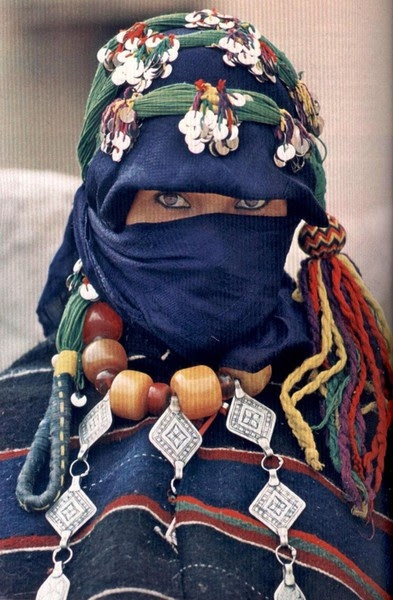

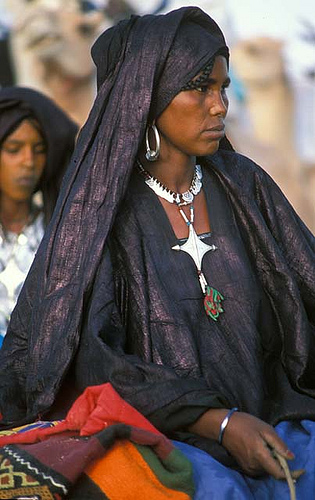

Beautiful veiled Tuareg woman from Libya. Eric Lafforgue

The Tuaregs live in five principal north-western African countries, particularly in southern Algeria, southwestern Libya, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. Fewer numbers Chad and Nigeria. The population distribution of Tuaregs is quite scanty, however, the unofficial estimates suggest that their total number in the region of approximately 4.5 million. Out of this sum, 85% of them resides in Mali and Niger and the rest between Algeria and Libya. And from the same estimates, they make up from 10% to 20% of the total population of Niger and Mali.

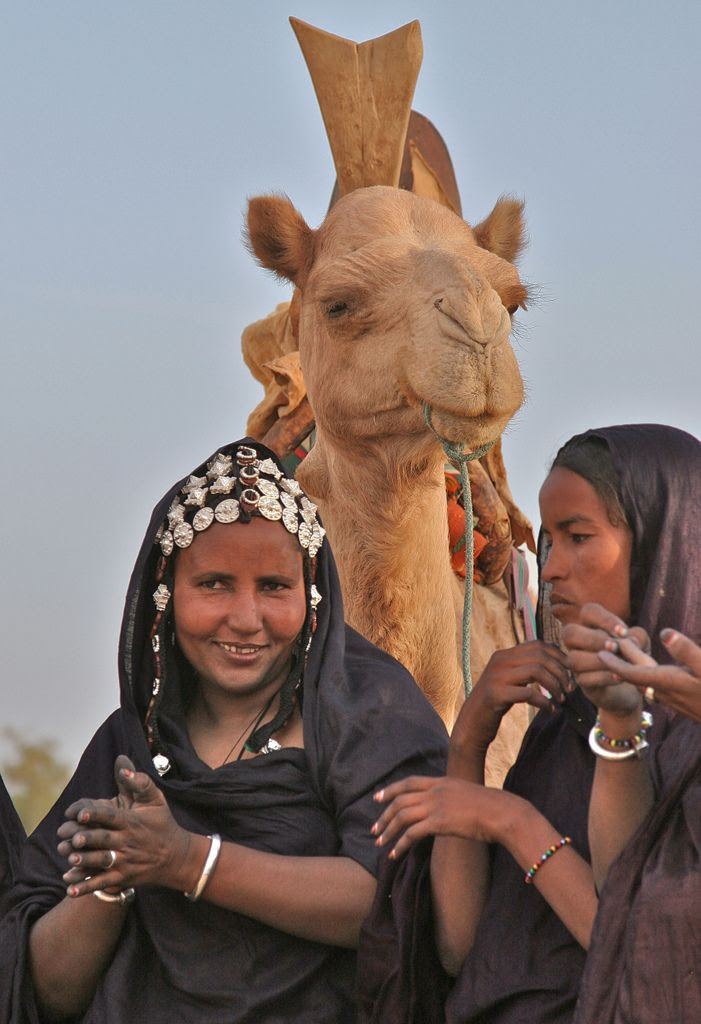

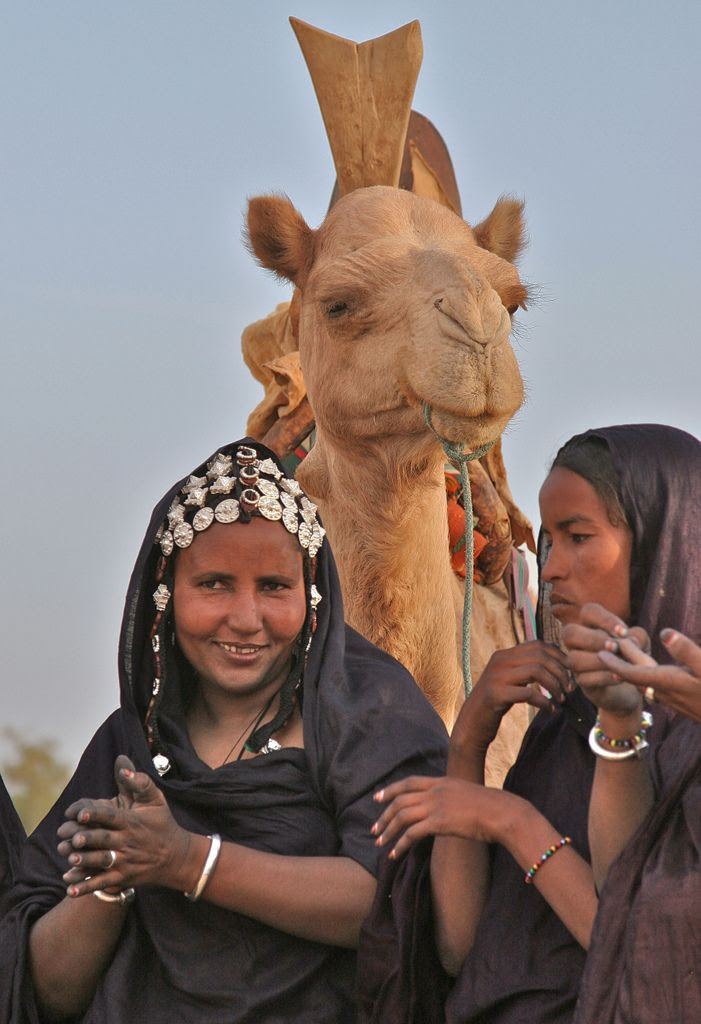

Touaregs at the Festival au Desert near Timbuktu, Mali

The population of the Libyan Tuaregs is approximately 10,000 Ajjer Tuaregs. About 8,000 Ajjer live along the Algerian border while the rest (2,000) settles in the Oasis of Ghat in the south west of Libya Prasse (Ibid) and Migdalovitz (1989). Tuaregs live in desert areas stretching from the south, Libya to northern Mali, in the Fezzan region of Libya; they are located in the Hoggar region of Algeria Veugdon. In Mali, there are provinces of the Touareg and Ozoad Adgag, but their presence in Niger is mainly in the region of Ayer.

![]()

Tuareg man at Ubari Lakes, Libya

In desert terms, the Tuareg people inhabit a large area, covering almost all the middle and western Sahara and the north-central Sahel. In Tuareg terms, the Sahara is not one desert but many, so they call it Tinariwen ("the Deserts"). Among the many deserts in Africa, there is the true desert Ténéré. Other deserts are more and less arid, flat and mountainous: Adrar, Tagant, Tawat (Touat) Tanezrouft, Adghagh n Fughas, Tamasna, Azawagh, Adar, Damargu, Tagama, Manga, Ayr, Tarramit (Termit), Kawar, Djado, Tadmait, Admer, Igharghar, Ahaggar, Tassili n'Ajjer, Tadrart, Idhan, Tanghart, Fezzan, Tibesti, Kalansho, Libyan Desert, etc.

While there is little conflict about the driest parts of Tuareg territory, many of the water sources and pastures they need for cattle breeding get fenced off by absentee landlords, impoverishing some Tuareg communities. There is also an unresolved land conflict about many stretches of farm land just south of the Sahara. Tuareg often also claim ownership over these lands and over the crop and property of the impoverished Rimaite-people, farming them.

![]()

Tuareg has been, until recently, experts familiar with the sub-Saharan pathways by helping the movement of convoys. They do these through their time-honored patience, courage and knowledge of the whereabouts of the water as well their command the stars that guides them. The clear desert skies allowed the Tuareg to be keen observers. Tuareg celestial objects include:

Azzag Willi (Venus), which indicates the time for milking the goats

Shet Ahad (Pleiades), the seven sisters of the night

Amanar (Orion (constellation)), the warrior of the desert

Talemt (Ursa Major), the she-camel

Awara (Ursa Minor), the baby camel

![]()

Tuaregs from Libya

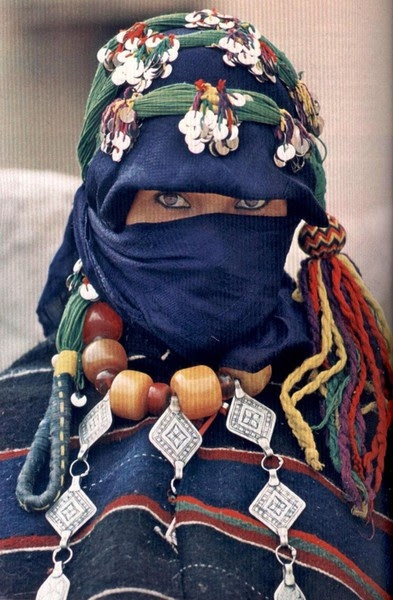

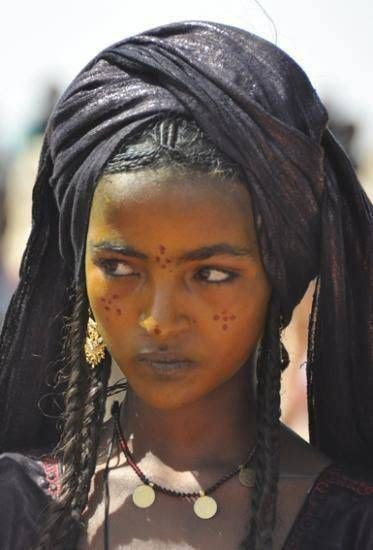

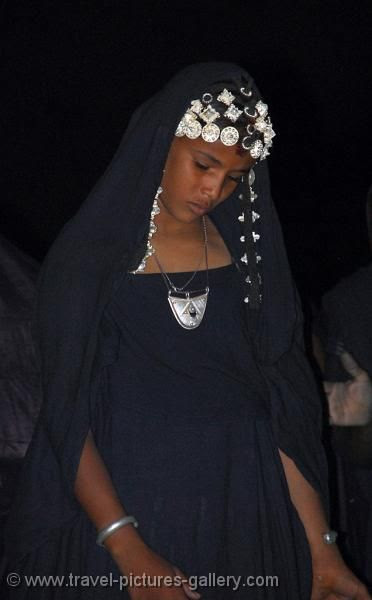

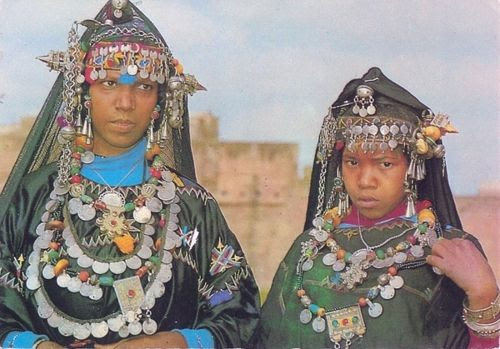

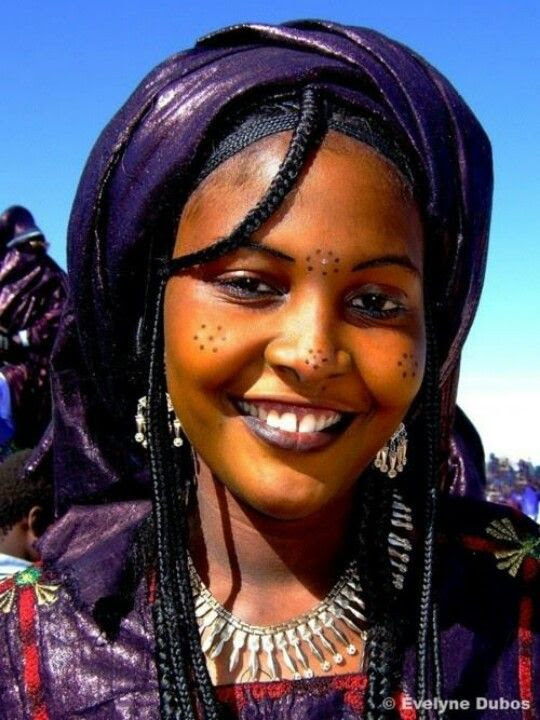

They Tuareg known internationally by their popular name "the Blue Men of the Sahara," "The Masked people" or "Men of the Veil," because of the indigo colour of the veils and other clothing which their men wear, which sometimes stains the skin underneath. The men only wear this cloth and not the women. Men begin wearing a veil at the age 25.

![]()

Touareg man from Niger

Tuareg merchants were responsible for bringing goods from these cities to the north. From there they were distributed throughout the world. Because of the nature of transport and the limited space available in caravans, Tuareg usually traded in luxury items, things which took up little space and on which a large profit could be made.

Tuaregs in their desert environment,Timbuktu, Mali

Tuareg were also responsible for bringing enslaved people from the north to west Africa to be sold to Europeans and Middle Easterners. Many Tuareg settled into the communities with which they traded, serving as local merchants.

![]()

The Name Tuareg/Toureg

The name Tuareg is an Arabic term meaning "abandoned by God," "ways" or "paths taken". According to some researchers - the word Touareg is taken from the word "Tareka"/"Targa" a valley in the region of Fezzan in Libya. So the name is of Berber origin and is taken from a place in Libya, not the name of the Muslim commander Tariq bin Ziyad, as some people claim. Thus name Tuareg was borrowed from the Berbers living closer to the Mediterranean coast, and was adopted from them into English, French and German during the colonial period. The Berber noun targa means "drainage channel" and by extension "arable land, garden". It designated the Wadi al-Haya area between Sabha and Ubari and is rendered in Arabic as bilad al-khayr "good land".

In The Ottoman Empire the Tuareg were called Tevarikler, however, the Tuaregs call themselves Imuhagh, or Imushagh (cognate to northern Berber Imazighen). Imuhagh is translated as 'free men," referring to the Tuareg "nobility", to the exclusion of the artisan client castes and slaves. The term for a Tuareg man is Amajagh (var. Amashegh, Amahagh), the term for a woman Tamajaq (var. Tamasheq, Tamahaq, Timajaghen).

![]()

Tuareg man with a sword

The spelling variants given reflect the variety of the Tuareg dialects, but they all reflect the same linguistic root. Some Tuaregs preferred to be called Limajgn or Temasheq; and were akin to Amazigh, meaning free men, they became a hybrid by combining in their blood with several races such as Targi, Arabic and Africans, due to the living with the Arabs in the north and with the black Africans in the South.

Also encountered in ethnographic literature of the early 20th century is the name Kel Tagelmust "People of the Veil" and "the Blue People" (for the indigo colour of their veils and other clothing, which sometimes stains the skin underneath.

![]()

Tuareg men "the blue people"

Tuareg Tribes (Cole)

Tuaregs word "Cole" which means "the people," is used for the identification of their tribal branches. there are major tribal confederations divided geographically into two main groups, namely:

(1)Tuareg tribes in desert of southern Algeria and the Fezzan in Libya has the most important tribes and they are as follows:

*Cole Hgar and Cole Aaajer in the desert of Algeria,

*Limngazn ,Oragen and Cole Aaajer in Fezzan and the city of Ghadames in Libya at the confluence of the borders with Tunisia and Algeria.

(2)Tuareg tribes of the coast, including:

*Cole Ayer and Cole Lmadn in Niger.

*Cole Litram, Cole Adraaar, Cole Tdmokt , Cole Ansar ( El Ansar), and Cole Alsswoq (traders) and the other in the Republic of Mali.

![]()

Tuareg kids

Language

The Tuareg speak a Berber language known as Tamajaq (also called Tamasheq or Tamahaq, according to the region where it is spoken), which appears to have several dialects spoken in different regions (Greenberg, 1970). The language is called Tamasheq by western Tuareg in Mali, Tamahaq among Algerian and Libyan Tuareg, and Tamajaq in the Azawagh and Aïr regions, Niger.

![]()

Tuareg woman from Timbuctu, Mali

The Tuareg distinguished themselves from other Berbers during their ancient times in Amazigh by preserving the dialect of Tamazight "Hackler" and they write their letters "Tifinagh" from right to left and from top to bottom and vice versa. Tifinagh (also called Shifinagh and Tifinar) is Tuareg Tamajaq writing system. The origins of "Tifinagh" remain unclear. An old version of Tifinagh, also known as Libyco-Berber, dates to between the 3rd century BC and the 3rd century AD in northwestern Africa (Gaudio, 1993).

Ancient Touareg Tifinagh script (tablet)

The Tuareg’s Tifinagh alphabet is composed of simple geometrical signs, it contains 21 to 27 signs, and are used according to the region. The Tifinagh language is written by tradition on stones, trunks and in the sand and is very difficult to read. French missionary Charles de Foucauld famously compiled a dictionary of the Tuareg language.

Nowadays one can see the Tifinagh’s letters still in the mountains and caves, an archeological evidence to the existence of the Tuareg in the desert since ancient times. According to some sources, the Berber dialect they speak is already one of the ancient Arabic dialects.

Though they think of themselves as a big unity the Tuareg are divided into several tribes and clans. Symbolizing their identity they call themselves "Cole Tmashek“, the people who speaks Tamashek.

History

The origin of Tuaregs who had gain the character of «Lords of desert» due to their persistent ability to confront and challenge the circumstances of geography and harsh climate is shrouded in mystery. No one knows the true origin of the Tuareg, where they came from or when they arrived in the Sahara. There are many schools of thought about the origins of the Tuareg.

![]()

Touareg people of Mali.

Historically, the Tuareg were recorded by the Greek historian Herodotus in the 5th Century BC in his travelogue during his travels to ancient Egypt and some parts of North Africa.

Ibn Battuta in his writings about his famous trips in Africa had this to say about the Tuareg: "They are Morabiteen state assets, and generally belong to the majority of the Touareg tribes Sanhaja.” Ibn Khaldun called the Tuareg masked people and like all Arab historians he classified them in the second layer of the "Sanhaja" In his words there are of many areas including "Kazolah", "Lamtonah", "Misratah" , "Laamtah" and "Rikah ". Some historians also aver that Tuaregs are people of Berbers extraction who appeared in North Africa and were one of the tribes of prehistoric races.

Frenchman Gustave Le Bon makes an interesting observation that the black hair Tuaregs were Berbers who migrated from the shores of the Euphrates and north of the countries inhabited by the Arabs, whilst the blond hair and blue eyes Tuaregs migrated from as far as Europe and were of Caucasoid blood. He postulated that the evidence could be found by comparing the stone monuments in Africa and the stone monuments discovered in northern Europe that shows same rock art of Tuaregs (Abual-Qasim Muhammad Crowe. Abdullah shareat. Dar Maghreb -Tunisia, p.12).

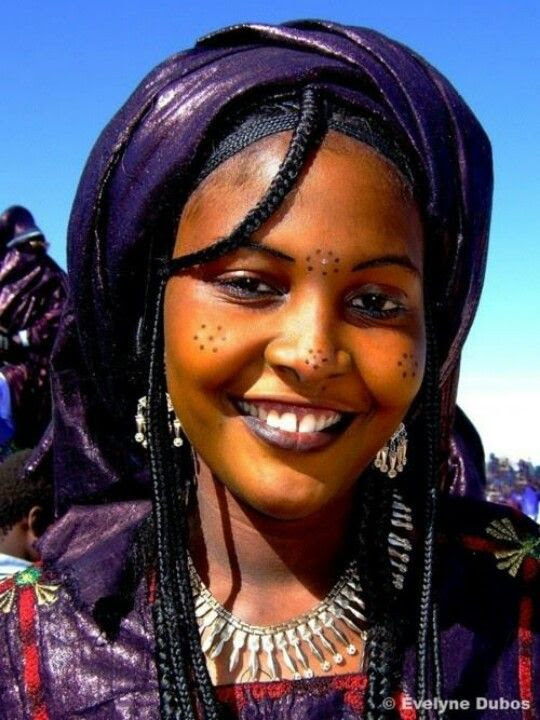

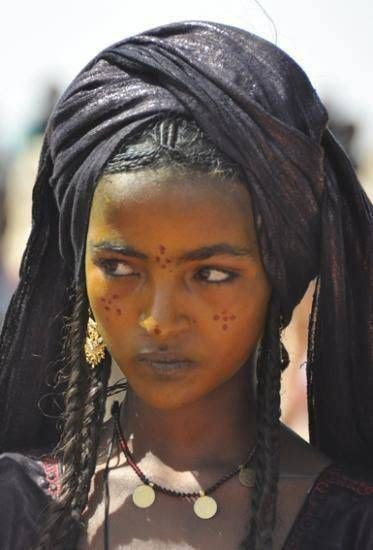

Tuareg girls

Abdul Qadir Jami Ferry said the word 'Touareg" is collection of the word Altargi, which is the name that the Arabs called the proportion of the Berber tribes living in the desert (Targa areas) of the ocean (Atlantic) close to Ghadames (Arabs Touareg of the Sahara, Akoshat Mohammed Said. Centre for Study and Research on the Sahara, 1989, p.27).

Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, right, meets Touareg men in Ain Salah,Algeria

From their Oral history, when one ask a Tuareg about their origin, they often assert that they originated from the Hamiriya in Yemen. From there they came to settle at Tafilalt and expanded southward from the Tafilalt region into the Sahel under their legendary queen Tin Hinan, who is assumed to have lived in the 4th or 5th century. Tin Hinan is credited in Tuareg lore with uniting the ancestral tribes and founding the unique culture that continues to the present day. At Abalessa, a grave traditionally held to be hers has been scientifically studied.

Tin Hinan Queen of Hoggar (today South Algeria)

However, the authentic information about the Tuareg origin is the consensus by historians who assert that Tuaregs descended from the Amazigh branch of Berber ancestors who lived in North Africa some centuries ago. This assertion that Tuaregs are of North African origin is supported by recent genetics studies into Tuareg`s Y-Chrosome DNA (Y chromosomes and mtDNA of Tuareg nomads from the African Sahel) and was published in European Journal of Human Genetics (2010). The studies found out that E1b1b1b (E-M81), the major haplogroup in Tuaregs, is the most common Y chromosome haplogroup in North Africa, dominated by its sub-clade E-M183. It is thought to have originated in North Africa 5,600 years ago.

![]()

The parent clade E1b1b originated in East Africa. Colloquially referred to as the Berber marker for its prevalence among Mozabite, Middle Atlas, Kabyle people and other Berber groups, E-M81 is also predominant among other North African groups. It reaches frequencies of up to 100 percent in some parts of the Maghreb.

![]()

Tuareg refugee camp in Burkina Faso

Y-Dna haplogroups, passed on exclusively through the paternal line, were found at the following frequencies in Tuaregs:

The other major haplogroup is E1b1a mainly found in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Overall, a cline appears, with Algerian Tuaregs being closer to other Berbers and Arabs, and those from southern Mali being more similar to Sub-Saharan Africans, see also: Deep into the roots of the Libyan Tuareg: a genetic survey of their paternal heritage

So as it stands, prior to around 1200 B.C., the North African ancestors of the Tuareg lived on the northern fringes of the Sahara, like most other Berber populations - but the introduction of the horse into North Africa in the mid-second millennium B.C. (and then the camel in the first century B.C.) enabled them to expand southwards across the desert. In medieval and early modern times, they established a succession of powerful desert federations which clashed with each other and with black-African states on the southern fringes of the Sahara.

![]()

By the 10th century A.D., the Tuareg had helped introduce Islam to West Africa, while economically they prospered from their control of the trans-Saharan gold, salt and slave trades. Indeed, Tuareg slave-raiding made them widely feared among sub-Saharan Africans.

But, just as the Tuareg had their powerful political structures and identities, so did the black-African population of southern Mali, who established the medieval Songhai and Mali empires - the latter name being resurrected as the name of the modern state.

![]()

Tuareg from Algeria

Tuareg territory covered (and still covers) not only northern Mali, but western Niger, southern Algeria and southwest Libya. And yet - like the Kurds and the Lapps and many other peoples - their land is divided between internationally recognized modern nation states.

The "partition" of the Tuaregs' desert land was carried out by the French in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Their vast territory merely formed the peripheral desert hinterlands of French coastal or riverine colonies in North and West Africa. The French colonial authorities thought that the desert was economically worthless.

The Tuareg territory was organised into confederations, each ruled by a supreme Chief (Amenokal), along with a counsel of elders from each tribe. These confederations are sometimes called "Drum Groups" after the Amenokal's symbol of authority, a drum. Clan (Tewsit) elders, called Imegharan (wisemen), are chosen to assist the chief of the confederation. Historically, there are seven recent major confederations:

Kel Ajjer or Azjar: centre is the oasis of Aghat (Ghat).

Kel Ahaggar, in Ahaggar mountains.

Kel Adagh, or Kel Assuk: Kidal, and Tin Buktu

Iwillimmidan Kel Ataram, or Western Iwillimmidan: Ménaka, and Azawagh region (Mali)

Iwillimmidan Kel Denneg, or Eastern Iwillimmidan: Tchin-Tabaraden, Abalagh, Teliya Azawagh (Niger).

Kel Ayr: Assodé, Agadez, In Gal, Timia and Ifrwan.

Kel Gres: Zinder and Tanut (Tanout) and south into northern Nigeria.

Kel Owey: Aïr Massif, seasonally south to Tessaoua (Niger)

In the late 19th century, the Tuareg resisted the French colonial invasion of their Central Saharan homelands. Tuareg broadswords were no match for the more advanced weapons of French troops. After numerous massacres on both sides, the Tuareg were subdued and required to sign treaties in Mali 1905 and Niger 1917. In southern Morocco and Algeria, the French met some of the strongest resistance from the Ahaggar Tuareg. Their Amenokal, traditional chief Moussa ag Amastan, fought numerous battles in defence of the region. Finally, Tuareg territories were taken under French governance, and their confederations were largely dismantled and reorganised

![]()

Economy

Subsistance and Commercial Activities.

The Tuareg are a pastoral people, having an economy based on livestock breeding, trading, and agriculture.

Traditionally, occupations corresponded to social-stratum affiliation, determined by descent. Tuareg are distinguished in their native language as the Imouhar, meaning the free people. Nobles controlled the caravan trade, owned most camels, and remained more nomadic, coming into oases only to collect a proportion of the harvest from their client and servile peoples.

Here are different types of caravans:

caravans transporting food: dates, millet, dried meat, dried Tuareg cheese, butter etc.

caravans transporting garments, alasho indigo turbans, leather products, ostrich feathers,

caravans transporting salt: salt caravans used for exchange against other products.

caravans transporting nothing but made to sell and buy camels.

![]()

Oasis In The Libyan Desert

Salt mines or salines in the desert.

Tin Garaban near Ghat in Azjar, Libya.

Amadghor in Ahaggar, Algeria.

Todennit in Tanezruft desert, Mali.

Tagidda N Tesemt in Azawagh, Niger

Fashi in Ténéré desert, Niger

Bilma in Kawar, Niger

Tributary groups raided and traded for nobles and also herded smaller livestock, such as goats, in usufruct relationships with nobles. Peoples of varying degrees of client and servile status performed domestic and herding labor for nobles. Smiths manufactured jewelry and household tools and performed praise songs for noble patron families, serving as important oral historians and political intermediaries. Owing to natural disasters and political tensions, it is now increasingly difficult to make a living solely from nomadic stockbreeding.

![]()

Thus, social stratum, occupation, and socioeconomic status tend to be less coincident. Most rural Tareg today combine subsistence methods, practicing herding, oasis gardening, caravan trading, and migrant labor. Nomadic stockbreeding still confers great prestige, however, and gardening remains stigmatized as a servile occupation. Other careers being pursued in the late twentieth century include creating art for tourists, at which smiths are particularly active, as artisans in towns, and guarding houses, also in the towns. On oases, crops include millet, barley, wheat, maize, onions, tomatoes, and dates.

![]()

A contemporary variant is occurring in northern Niger, in a traditionally Tuareg territory that comprises most of the uranium-rich land of the country. The central government in Niamey has shown itself unwilling to cede control of the highly profitable mining to indigenous clans. The Tuareg are determined not to relinquish the prospect of substantial economic benefit. The French government has independently tried to defend a French firm, Areva, established in Niger for fifty years and now mining the massive Imouraren deposit.

![]()

Additional complaints against Areva are that it is: "...plundering...the natural resources and [draining] the fossil deposits. It is undoubtedly an ecological catastrophe". These mines yield uranium ores, which are then processed to produce yellowcake, crucial to the nuclear power industry (as well as aspirational nuclear powers). In 2007, some Tuareg people in Niger allied themselves with the Niger Movement for Justice (MNJ), a rebel group operating in the north of the country. During 2004–2007, U.S. Special Forces teams trained Tuareg units of the Nigerien Army in the Sahel region as part of the Trans-Sahara Counter-Terrorism Partnership. Some of these trainees are reported to have fought in the 2007 rebellion within the MNJ. The goal of these Tuareg appears to be economic and political control of ancestral lands, rather than operating from religious and political ideologies.

Despite the Sahara's erratic and unpredictable rainfall patterns, the Tuareg have managed to survive in the hostile desert environment for centuries. Over recent years however, depletion of water by the uranium exploitation process combined with the effects of climate change are threatening their ability to subsist. Uranium mining has diminished and degraded Tuareg grazing lands. Not only does the mining industry produce radioactive waste that can contaminate crucial sources of ground water resulting in cancer, stillbirths, and genetic defects but it also uses up huge quantities of water in a region where water is already scarce.

![]()

This is exacerbated by the increased rate of desertification thought to be the result of global warming. Lack of water forces the Tuareg to compete with southern farming communities for scarce resources and this has led to tensions and clashes between these communities. The precise levels of environmental and social impact of the mining industry have proved difficult to monitor due to governmental obstruction.

Food

Taguella is a flat bread made from millet, a grain, which is cooked on charcoals in the sand and eaten with a heavy sauce. Millet porridge is a staple much like ugali and fufu. Millet is boiled with water to make a pap and eaten with milk or a heavy sauce.

Common dairy foods are goat's and camel's milk, as well as cheese and yogurt made from them. Eghajira is a thick beverage drunk with a ladle. It is made by pounding millet, goat cheese, dates, milk and sugar and is served on festivals like Eid ul-Fitr and Eid al-Adha. A popular tea, gunpowder tea, is poured three times in and out of a tea pot with mint and sugar into tiny glasses.

Preparation of communal meal for extended Tuareg family

Trade

The caravan trade, although today less important than formerly, persists in the region between the Air Mountains and Kano, Nigeria. Men from the Aïr spend five to seven months each year on camel caravans, traveling to Bilma for dates and salt, and then to Kano to trade them for millet and other foodstuffs, household tools, and luxury items such as spices, perfume, and cloth.

Division of Labor

Most camel herding is still done by men; although women may inherit and own camels, they tend to own and herd more goats, sheep, and donkeys. Caravan trade is exclusively conducted by men. A woman may, however, indirectly participate in the caravan trade by sending her camels with a male relative, who returns with goods for her. Men plant and irrigate gardens, and women harvest the crops. Whereas women may own gardens and date palms, they leave the work of tending them to male relatives.

![]()

Gender Construction

The Tuareg are "largely matrilineal". Tuareg women have high status compared with their Arab counterparts. They enjoy considerable independence, even if they are married they are entitled to go into business with or without their husbands permission.

They are free to engage in any form of business, transact business with men and even host their male friends and business partners in the presence of their husbands in the house. As a result of this practice some anthropologists considers the Touareg society as a matriarchal society that reveres and respect women.

![]()

Amazigh Touaregs maintained this matriarchal characteristics even though most of other Berbers in the North African countries of Morocco, Algeria, Libya and Tunisia practiced highly patriarchal culture. Touareg women do not put a mask on their faces, but their men do. The most famous figure in the history of the Touareg Berbers was a woman named Tin Henin, a leader who founded the Kingdom of great OhakarAmazigh.

![]()

In the center of the Tuareg tent is always a small table that is used to serve tea on. There is another table generally allocated to guests and passer-bys. It is their habits that when someone is visiting them in their houses women go outside and comes back carrying vessels filled with camel milk. This is a sign 'To welcome the newcomers," whether he or she was a family member, they see them as guests or visitors coming in after a long journey.

The Touareg follow their leader (head) of the tribe, called the «Omnwokl». And he ensures women have special place in the community. Apart from women having special place in their communities, they enjoy great freedom in matters such as choosing a life partner and taking care of home affairs. Polygamy is forbidden for women. Tuareg divorcee women often boast by calling the man the men they have divorced as "Ohasis." it means “freed from any obligation!”

Kinship

Kin Groups and Descent

The introduction of Islam in the seventh century a.d. had the long-term effect of superimposing patrilineal institutions upon traditional matriliny. Formerly, each matrilineal clan was linked to a part of an animal, over which that clan had rights (Casajus 1987; Lhote 1953; Nicolaisen 1963; Norris 1975, 30).

Matrilineal clans were traditionally important as corporate groups, and they still exert varying degrees of influence among the different Tuareg confederations. Most Tuareg today are bilateral in descent and inheritance systems (Murphy 1964; 1967). Descent-group allegience is through the mother, social-stratum affiliation is through the father, and political office, in most groups, passes from father to son.

Kinship Terminology

Tuareg personal names are used most frequently in addressing all descendants and kin of one's own generation, although cousins frequently address one another by their respective classificatory kinship terms. Kin of the second ascending generation may be addressed using the classificatory terms anna (mother) and abba (father), as may brothers and sisters of parents, although this is variable.

Young Tuareg nomad

Most ascendants, particularly those who are considerably older and on the paternal side, are usually addressed with the respectful term amghar (masc.) or tamghart (fem.). The most frequently heard kinship term is abobaz, denoting "cousin," used in a classificatory sense.

Tuareg enjoy more relaxed, familiar relationships with the maternal side, which is known as tedis, or "stomach" and associated with emotional and affective support, and more reserved, distant relations with the paternal side, which is known as arum, or "back" and associated with material suport and authority over Ego. There are joking relationships with cousins; relationships with affines are characterized by extreme reserve. Youths should not pronounce the names of deceased ancestors.

Marriage and Family

Marriage

Cultural ideals are social-stratum endogamy and close-cousin marriage. In the towns, both these patterns are breaking down. In rural areas, class endogamy remains strong, but many individuals marry close relatives only to please their mothers; they subsequently divorce and marry nonrelatives. Some prosperous gardeners, chiefs, and Islamic scholars practice polygyny, contrary to the nomadic Tuareg monogamous tradition and contrary to many women's wishes; intolerant of co-wives, many women initiate divorces.

Tuareg Marriage ceremony

when a Tuareg young man admires young girl whom he want to marry, the young man selects a group of friends and some family members to accompany him off and pitch a camp near the tent of the girl's family. The delegation of the young man then proceed to meet the girl`s father and inquire about the girl in order to seek her hand in marriage. If the girl`s father agree, he will identify a dowry for the young man to pay.

The young man`s delegation will then return to give him the message about the dowry. If the young man agrees to the dowry he will appoint a proxy as custom requires in the Tuareg. For the groom cannot have his bride until those closest to him carries dowry to where the marriage is contracted. The dowry for the nobles is seven camels, and for the "gor" (the slaves) two heads of goats.

After paying the dowry in full, the mother of the bride is given a gift called "Tagst." It is a bull or a camel, and when offering these gifts, a group of women also start singing and dancing and demanding a gift of the groom. As customs demand, the groom gives them an oxen which then slaughtered in front of all the women.

The wedding ceremony of the Tuaregs lasts 3 days, and after that the groom bring the rest of his marriage stuffs such as sugar, green tea and shoes. The ceremony continue then for three more days. In this ceremony they distribute the gifts to the people of the district equally.

In the first night of marriage the groom considers his bride as his mother!! On the second day he considers his bride in the night as his sister!! And on the third night the bride becomes his wife and he justify that by making sweet love to his bride and also assuring her of a wonderful trip of a lifetime.

In the morning friends of the groom come to visit him with the fat hump of a camel. If the bride was a virgin they do not eat the hump but they will cook it and return it to women amidst sounds of joy which indicates that the bride is a virgin. But if the bride was not virgin they eat the hump of the camel and the bride's family would know that their daughter is not a virgin. When such a thing happen the bride`s family becomes engulfed in a total disgrace!

Tuareg bride and the groom dancing during wedding festivities, Mali

After this ritual, the wedding celebration continues for a full week where the bride goes out with her friends whilst the groom stays in the tent without seeing his father or mother.

![]()

Tuareg bride, Burkina Faso

Domestic Unit

Tuareg groups vary in postmarital-residence rules. Some groups practice virilocal residence, others uxorilocal residence. The latter is more common among caravanning groups in the Aïr, such as the Kel Ewey, who adhere to uxorilocal residence for the first two to three years of marriage, during which time the husband meets the bride-wealth payments, fulfills obligations of groom-service, and offers gifts to his parents-in-law.

![]()

Upon fulfillment of these obligations, the couple may choose where to live, and the young married woman may disengage her animals from her herds and build a separate kitchen, apart from her mother's.

Inheritance

Patrilineal inheritance, arising from Islamic influence, prevails, unless the deceased indicated otherwise, before death, in writing, in the presence of a witness: two-thirds of the property goes to the sons, one-third to the daughters. Alternative inheritance forms, stemming from ancient matriliny, include "living milk herds" (animals reserved for sisters, daughters, and nieces) and various pre-inheritance gifts.

Socialization

Fathers are considered disciplinarians, yet other men, particularly maternal uncles, often play and joke with small children. Women who lack their own daughters often adopt nieces to assist in housework. Although many men are often absent (while traveling), Tuareg children are nonetheless socialized into distinct, culturally defined masculine and feminine gender roles because male authority figures—chiefs, Islamic scholars, and wealthy gardeners—remain at home rather than departing on caravans or engaging in migrant labor, and these men exert considerable influence on young boys, who attend Quranic schools and assist in male tasks such as gardening and herding. Young girls tend to remain nearer home, assisting their mothers with household chores, although women and girls also herd animals.

![]()

Traditionally, Tuareg society is hierarchical, with nobility and vassals. Each Tuareg clan (tawshet) is made up of several family groups, each led by its chief, the amghar. A series of tawsheten (plural of tawshet) may bond together under an Amenokal, forming a Kel clan confederation.

![]()

Tuareg self-identification is related only to their specific Kel, which means "those of". E.g. Kel Dinnig (those of the east), Kel Ataram (those of the west). The position of amghar is hereditary through a matrilineal principle, it is usual for the son of a sister of the incumbent chieftain to succeed to his position. The amenokal is elected in a ritual which differs between groups, the individual amghar who lead the clans making up the confederation usually have the deciding voice.

Nobility and vassals: The work of pastoralism was specialized according to social class. Tels are ruled by the imúšaɣ (Imajaghan, The Proud and Free) nobility, warrior-aristocrats who organized group defense, livestock raids, and the long-distance caravan trade. Below them were a number of specialised métier castes. The ímɣad (Imghad, singular Amghid), the second rank of Tuareg society, were free vassal-herdsmen and warriors, who pastured and tended most of the confederation's livestock. Formerly enslaved vassals of specific Imajaghan, they are said by tradition to be descended from nobility in the distant past, and thus maintain a degree of social distance from lower orders. Traditionally, some merchant castes had a higher status than all but the nobility among their more settled compatriots to the south. With time, the difference between the two castes has eroded in some places, following the economic fortunes of the two groups.

Imajaghan have traditionally disdained certain types of labor and prided themselves in their warrior skills. The existence of lower servile and semi-servile classes has allowed for the development of highly ritualised poetic, sport, and courtship traditions among the Imajaghan. Following colonial subjection, independence, and the famines of the 1970s and 1980s, noble classes have more and more been forced to abandon their caste differences. They have taken on labor and lifestyles they might traditionally have rejected.

Touareg men at the Essakane Festival (Mali) in january 2007

Client castes: After the adoption of Islam, a separate class of religious clerics, the Ineslemen or marabouts, also became integral to Tuareg social structure. Following the decimation of many clans' noble Imajaghan caste in the colonial wars of the 19th and 20th centuries, the Ineslemen gained leadership in some clans, despite their often servile origins. Traditionally Ineslemen clans were not armed. They provided spiritual guidance for the nobility, and received protection and alms in return.

Inhædˤæn (Inadan), were a blacksmith-client caste who fabricated and repaired the saddles, tools, household equipment and other material needs of the community. They were often, in addition to craftwork, the repository of oral traditions and poetry. They were also often musicians and played an important role in many ceremonies. Their origins are unclear, one theory proposing an original Jewish derivation. They had their own special dialect or secret language. Because of their association with fire, iron and precious metals and their reputation for cunning tradesmanship the ordinary Tuareg regarded them with a mixture of awe and distrust.

Tuareg peasants: The people who farm oases in Tuareg-dominated areas form a distinct group known as izeggaghan (or hartani in Arabic). Their origins are unclear but they often speak both Tuareg dialects and Arabic, though a few communities are Songhay speakers. Traditionally they worked land owned by a Tuareg noble or vassal family, being allowed to keep a fifth part of their produce. Their Tuareg patrons were usually responsible for supplying agricultural tools, seed and clothing.

Bonded castes and slaves: Like other major ethnic groups in West Africa, the Tuareg once held slaves (éklan / Ikelan in Tamasheq, Bouzou in Hausa, Bella in Songhai). The slaves called éklan once formed a distinct social class in Tuareg society. Eklan formed distinct sub-communities; they were a class held in an inherited serf-like condition, common among societies in precolonial West Africa.

When French colonial governments were established, they passed legislation to abolish slavery, but did not enforce it. Some commentators believe the French interest was directed more at dismantling the traditional Tuareg political economy, which depended on slave labor for herding, than at freeing the slaves. Historian Martin Klein reports that there was a large scale attempt by French West African authorities to liberate slaves and other bonded castes in Tuareg areas following the 1914–1916 Firouan revolt. Despite this, French officials following the Second World War reported there were some 50,000 "Bella" under direct control of Tuareg masters in the Gao–Timbuktu areas of French Soudan alone. This was at least four decades after French declarations of mass freedom had happened in other areas of the colony. In 1946, a series of mass desertions of Tuareg slaves and bonded communities began in Nioro and later in Menaka, quickly spreading along the Niger River valley. In the first decade of the 20th century, French administrators in southern Tuareg areas of French Sudan estimated "free" to "servile" Tuareg populations at ratios of 1 to 8 or 9. At the same time the servile "rimaibe" population of the Masina Fulbe, roughly equivalent to the Bella, made up between 70% to 80% of the Fulbe population, while servile Songhai groups around Gao made up some 2/3 to 3/4 of the total Songhai population. Klein concludes that roughly 50% of the population of French Soudan at the beginning of the 20th century were in some servile or slave relationship.

While post-independence states have sought to outlaw slavery, results have been mixed. Traditional caste relationships have continued in many places, including the institution of slavery. According to the Travel Channel show, Bob Geldof in Africa, the descendants of those slaves known as the Bella are still slaves in all but name. In Niger, where the practice of slavery was outlawed in 2003, a study found that almost 8% of the population are still enslaved.

![]()

Social Control

In the traditional segmentary system, no leader had power over his followers solely by virtue of a position in a political hierarchy. Wealth was traditionally enough to guarantee influence. Nobles acted as managers of large firms and controlled most resources, although they constituted less than 10 percent of the population.

Even traditionally, however, there were no cut-and-dry free or slave statuses. Below the aristocracy were various dependents whose status derived from their position in the larger system (e.g., whether attached to a specific noble or noble section); they had varying degrees of freedom.

Tuareg assimilated outsiders, who formed the servile strata, on a model of fictive kinship: a noble owner was expected to be "like a father" to his slave. Vestiges of former tribute and client-patron systems persist today, but also encounter some resistance. On some oases, nobles still theoretically have rights to dates from date palms within gardens of former slaves, but nowadays the former slaves refuse to fetch them, obliging nobles to climb the trees and collect the dates themselves.

![]()

Conflict

In principle, members of the same confederation are not supposed to raid each other's livestock, but such raids do occur (Casajus 1987). In rural areas today, many local-level disputes are arbitrated by a council of elders and Islamic scholars who apply Quranic law, but individuals have the option of taking cases to secular courts in the towns.

Malian soldier speaks with Tuareg men Seydou (C) and Abdoul Hassan in the village of Tashek, outside Timbuktu,

Religious Beliefs

The local belief system, with its own cosmology and ritual, interweaves and overlaps with Islam rather than standing in opposition to it. In Islamic observances, men are more consistent about saying all the prescribed prayers, and they employ more Arabic loanwords, whereas women tend to use Tamacheq terms.

There is general agreement that Islam came from the West and spread into Aïr with the migration of Sufi mystics in the seventh century (Norris 1975). Tuareg initially resisted Islam and earned a reputation among North African Arabs for being lax about Islamic practices.

For example, local tradition did not require female chastity before marriage. In Tuareg groups more influenced by Quranic scholars, female chastity is becoming more important, but even these groups do not seclude women, and relations between the sexes are characterized by freedom of social interaction.

![]()

Religious Practitioners

In official religion, Quranic scholars, popularly called ineslemen, or marabouts, predominate in some clans, but anyone may become one through mastery of the Quran and exemplary practice of Islam. Marabouts are considered "people of God" and have obligations of generosity and hospitality. Marabouts are believed to possess special powers of benediction, al baraka. Quranic scholars are important in rites of passage and Islamic rituals, but smiths often act in these rituals, in roles complementary to those of the Quranic scholars. For example, at babies' name-days, held one week following a birth, the Quranic scholar pronounces the child's name as he cuts the throat of a ram, but smiths grill its meat, announce the name-day, and organize important evening festivals following it, at which they sing praise songs. With regard to weddings, a marabout marries a couple at the mosque, but smiths negotiate bride-wealth and preside over the evening festivals.

Ceremonies

Important rituals among Tuareg are rites of passage—namedays, weddings, and memorial/funeral feasts—as well as Islamic holidays and secular state holidays. In addition, there is male circumcision and the initial men's face-veil wrapping that takes place around the age of 18 years and that is central to the male gender role and the cultural values of reserve and modesty.

Touaregs at the Festival au Desert near Timbuktu, Mali

There are also spirit-possession exorcism rituals (Rasmussen 1995). Many rituals integrate Islamic and pre-Islamic elements in their symbolism, which incorporates references to matrilineal ancestresses, pre-Islamic spirits, the earth, fertility, and menstruation.

Tuareg celebration in Sbiba. Most of the men are wielding the takouba, the Tuareg sword.

The Desert Festival in Mali's Timbuktu provides one opportunity to see Tuareg culture and dance and hear their music. Other festivals include:

Cure Salee Festival in the oasis of In-Gall, Niger

Sabeiba Festival in Ganat (Djanet), Algeria

Shiriken Festival in Akabinu (Akoubounou), Niger

Takubelt Tuareg Festival in Mali

The 19th Ghat Festival in Libya | December 2013 In the annual event, Tuareg tribes from the region and tourists meet to celebrate Tuareg traditional culture, folklore and heritage in the ancient city of Ghat, lies in the south-west corner of Libya. Photos

Ghat Festival in Aghat (Ghat), Libya

Le Festival au Désert in Mali

Ghadames Tuareg Festival in Libya

Touaregs at the Festival au Desert near Timbuktu, Mali 2012

Arts.

In Tuareg culture, there is great appreciation of visual and aural arts. There is a large body of music, poetry, and song that is of central importance during courtship, rites of passage, and secular festivals.

![]()

Tuareg man with his sword during Fulani Gerewol festival

Men and women of diverse social origins dance, perform vocal and instrumental music, and are admired for their musical creativity; however, different genres of music and distinct dances and instruments are associated with the various social strata. There is also the sacred liturgical music of Islam, performed on Muslim holidays by marabouts, men, and older women.

Tuareg Amulet Khomeissa on leather

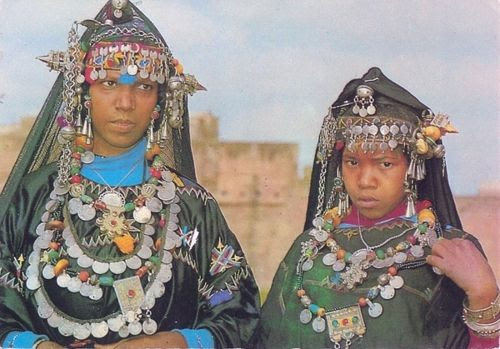

Much Tuareg art is in the form of metalwork (silver jewelry), dyed and embroidered leatherwork and metal saddle decorations called trik, and finely crafted swords. They also do some woodwork (delicately decorated spoons and ladles and carved camel saddles). The Inadan community makes traditional handicrafts.

Among their products are tanaghilt or zakkat (the 'Agadez Cross' or 'Croix d'Agadez'); the Tuareg sword (Takoba), many gold and silver-made necklaces called 'Takaza'; and earrings called 'Tizabaten'.

All these works are specialties of smiths, who formerly manufactured these products solely for their noble patrons. In rural areas, nobles still commission smiths to make these items, but in urban areas many smiths now sell jewelry and leather to tourists.

Tuareg jewelry seller

Music

Traditional Tuareg music has two major components: the monochord violin anzad played often during night parties and a small tambour covered with goatskin called tende, performed during camel and horse races, and other festivities. Traditional songs called Asak and Tisiway (poems) are sung by women and men during feasts and social occasions. Another popular Tuareg musical genre is takamba, characteristic for its Afro percussions.

Vocal music

tisiway: poems

tasikisikit: songs performed by women, accompanied by tende, men on camel back turn around

asak: songs accompanied by anzad monocord violin.

tahengemmit: slow songs sung by elder men

Children and youth music

Bellulla songs made by children playing with the lips

Fadangama small monocord instrument for children

Odili flute made from trunk of sorghum

Gidga small wooden instrument with irons sticks to make strident sounds

Tuareg singer Athmane Bali from Djanet, Algeria

Dance

One of the traditional dances of the nomadic Tuareg is the 'Tam Tam' where the men on camel circle the women while they play drums and chant.

tagest: dance made while seated, moving the head, the hands and the shoulders.

ewegh: strong dance performed by men, in couples and groups.

agabas: dance for modern ishumar guitars: women and men in groups.

Tuareg musicians of Amazigh

In the 1980s rebel fighters founded Tinariwen, a Tuareg band that fuses electric guitars and indigenous musical styles. Tinariwen is one of the best known and authentic Tuareg bands. Especially in areas that were cut off during the Tuareg rebellion (e.g., Adrar des Iforas), they were practically the only music available, which made them locally famous and their songs/lyrics (e.g. Abaraybone, ...) are well known by the locals.

![]()

They released their first CD in 2000, and toured in Europe and the United States in 2004. Tuareg guitar groups that followed in their path include Group Inerane and Group Bombino. The Niger-based band Etran Finatawa combines Tuareg and Wodaabe members, playing a combination of traditional instruments and electric guitars.

Many music groups emerged after the 1980s cultural revival. Among the Tartit, Imaran and known artists are: Abdallah Oumbadougou from Ayr, Baly Othmany of Djanet.

Clothing

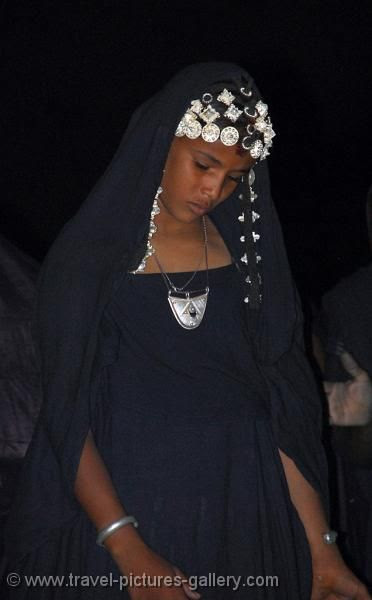

In Tuareg society women do not traditionally wear the veil, whereas men do. The most famous Tuareg symbol is the Tagelmust (also called éghéwed), referred to as a Cheche (pronounced "Shesh"), an often indigo blue-colored veil called Alasho.

The men's facial covering originates from the belief that such action wards off evil spirits. It may have related instrumentally from the need for protection from the harsh desert sands as well. It is a firmly established tradition, as is the wearing of amulets containing sacred objects and, recently, also verses from the Qur'an. Taking on the veil is associated with the rite of passage to manhood; men begin wearing a veil when they reach maturity. The veil usually conceals their face, excluding their eyes and the top of the nose.

tagelmust: turban – men

alasho: blue indigo veil – women and men

bukar: black cotton turban – men

tasuwart: women's veil

takatkat: shirt – women and men

takarbast: short shirt – women and men

akarbey: pants worn by men

afetek: loose shirt worn by women

afer: women's pagne

tari: large black pagne for winter season

bernuz: long woolen cloth for winter

akhebay: loose bright green or blue cloth for women

ighateman: shoes

iragazan: red leather sandals

ibuzagan: leather shoes

The Tuareg are sometimes called the "Blue People" because the indigo pigment in the cloth of their traditional robes and turbans stained their skin dark blue. The traditional indigo turban is still preferred for celebrations, and generally Tuareg wear clothing and turbans in a variety of colors.

![]()

Adornments

The women wear anklets, bracelets, silver beads and other adornments. Girls often wear adornments from their relatives and when they are married they tried to have their own. They have the right to wear the anklets, and the rest of the decorations known to women in general.

The men wear loose sleeves with embroidered pocket, and often possess a dagger or sword. The sword hilt is studded with silver and gold, precious stones and carved by the names of its owners.

Medicine

Health care among Tuareg today includes traditional herbal, Quranic, and ritual therapies, as well as Western medicine. Traditional medicine is more prevalent in rural communities because of geographic barriers and political tensions. Although local residents desire Western medicines, most Western-trained personnel tend to be non-Tuareg, and many Tuareg are suspicious or shy of outside medical practitioners (Rasmussen 1994). Therefore rural peoples tend to rely most upon traditional practitioners and remedies.

For example, Quranic scholars cure predominantly men with verses from the Quran and some psychological counseling techniques. Female herbalists cure predominantly women and children with leaves, roots, barks, and some holisitic techniques such as verbal incantations and laying on of hands. Practitioners called bokawa (a Hausa term; sing. boka ) cure with perfumes and other non-Quranic methods. In addition, spirit possession is cured by drummers.

Tuareg drummers

Death and Afterlife

In the Tuareg worldview, the soul (iman ) is more personalized than are spirits. It is seen as residing within the living individual, except during sleep, when it may rise and travel about. The souls of the deceased are free to roam, but usually do so in the vicinity of graves.

![]()

A dead soul sometimes brings news and, in return, demands a temporary wedding with its client. It is believed that the future may be foretold by sleeping on graves. Tuareg offer libations of dates to tombs of important marabouts and saints in order to obtain the al-baraka benediction. Beliefs about the afterlife (e.g., paradise) conform closely to those of official Islam.

![]()

Source: http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Tuareg.aspx

Photosource:http://www.brentstirton.com/index.php#mi=2&pt=1&pi=10000&s=55&p=16&a=3&at=0

![]()

Touareg sword dance

Touareg sword dance

![Africa | Tuareg woman photographed at the Iférouane Festival 2006. Niger | ©Daniele L]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![Tuareg bride by العقوري [ Libya Photographer ]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEj5EbouNg8nQIVriFZdAcZXsAOKcat72oMSpmzAH-RXfzrtL1x3_ikQdziHbPObhOYzApX5bCCxd3KGrsZzitGtmYMpv8UA4xreKh4NyTJCNwE4iwqRvm6rjzLDwXNOk2ZmM6glLs3KSCCYfMhsI8pEXjhqSbYkLbntaqrIj2nFSgdT8YmdVgxEjF80jh6lXP-BTzz-=s0-d)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![Tuareg Hospitality]()

![]()

Tuareg women, Agadez,Niger

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Amazigh Tuareg, Libya

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Beautiful veiled Tuareg woman from Libya. Eric Lafforgue

The Tuaregs live in five principal north-western African countries, particularly in southern Algeria, southwestern Libya, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. Fewer numbers Chad and Nigeria. The population distribution of Tuaregs is quite scanty, however, the unofficial estimates suggest that their total number in the region of approximately 4.5 million. Out of this sum, 85% of them resides in Mali and Niger and the rest between Algeria and Libya. And from the same estimates, they make up from 10% to 20% of the total population of Niger and Mali.

Touaregs at the Festival au Desert near Timbuktu, Mali

The population of the Libyan Tuaregs is approximately 10,000 Ajjer Tuaregs. About 8,000 Ajjer live along the Algerian border while the rest (2,000) settles in the Oasis of Ghat in the south west of Libya Prasse (Ibid) and Migdalovitz (1989). Tuaregs live in desert areas stretching from the south, Libya to northern Mali, in the Fezzan region of Libya; they are located in the Hoggar region of Algeria Veugdon. In Mali, there are provinces of the Touareg and Ozoad Adgag, but their presence in Niger is mainly in the region of Ayer.

Tuareg man at Ubari Lakes, Libya

In desert terms, the Tuareg people inhabit a large area, covering almost all the middle and western Sahara and the north-central Sahel. In Tuareg terms, the Sahara is not one desert but many, so they call it Tinariwen ("the Deserts"). Among the many deserts in Africa, there is the true desert Ténéré. Other deserts are more and less arid, flat and mountainous: Adrar, Tagant, Tawat (Touat) Tanezrouft, Adghagh n Fughas, Tamasna, Azawagh, Adar, Damargu, Tagama, Manga, Ayr, Tarramit (Termit), Kawar, Djado, Tadmait, Admer, Igharghar, Ahaggar, Tassili n'Ajjer, Tadrart, Idhan, Tanghart, Fezzan, Tibesti, Kalansho, Libyan Desert, etc.

While there is little conflict about the driest parts of Tuareg territory, many of the water sources and pastures they need for cattle breeding get fenced off by absentee landlords, impoverishing some Tuareg communities. There is also an unresolved land conflict about many stretches of farm land just south of the Sahara. Tuareg often also claim ownership over these lands and over the crop and property of the impoverished Rimaite-people, farming them.

Tuareg woman

Tuareg has been, until recently, experts familiar with the sub-Saharan pathways by helping the movement of convoys. They do these through their time-honored patience, courage and knowledge of the whereabouts of the water as well their command the stars that guides them. The clear desert skies allowed the Tuareg to be keen observers. Tuareg celestial objects include:

Azzag Willi (Venus), which indicates the time for milking the goats

Shet Ahad (Pleiades), the seven sisters of the night

Amanar (Orion (constellation)), the warrior of the desert

Talemt (Ursa Major), the she-camel

Awara (Ursa Minor), the baby camel

Tuaregs from Libya

They Tuareg known internationally by their popular name "the Blue Men of the Sahara," "The Masked people" or "Men of the Veil," because of the indigo colour of the veils and other clothing which their men wear, which sometimes stains the skin underneath. The men only wear this cloth and not the women. Men begin wearing a veil at the age 25.

Touareg man from Niger

Tuareg merchants were responsible for bringing goods from these cities to the north. From there they were distributed throughout the world. Because of the nature of transport and the limited space available in caravans, Tuareg usually traded in luxury items, things which took up little space and on which a large profit could be made.

Tuaregs in their desert environment,Timbuktu, Mali

Tuareg were also responsible for bringing enslaved people from the north to west Africa to be sold to Europeans and Middle Easterners. Many Tuareg settled into the communities with which they traded, serving as local merchants.

The Name Tuareg/Toureg

The name Tuareg is an Arabic term meaning "abandoned by God," "ways" or "paths taken". According to some researchers - the word Touareg is taken from the word "Tareka"/"Targa" a valley in the region of Fezzan in Libya. So the name is of Berber origin and is taken from a place in Libya, not the name of the Muslim commander Tariq bin Ziyad, as some people claim. Thus name Tuareg was borrowed from the Berbers living closer to the Mediterranean coast, and was adopted from them into English, French and German during the colonial period. The Berber noun targa means "drainage channel" and by extension "arable land, garden". It designated the Wadi al-Haya area between Sabha and Ubari and is rendered in Arabic as bilad al-khayr "good land".

In The Ottoman Empire the Tuareg were called Tevarikler, however, the Tuaregs call themselves Imuhagh, or Imushagh (cognate to northern Berber Imazighen). Imuhagh is translated as 'free men," referring to the Tuareg "nobility", to the exclusion of the artisan client castes and slaves. The term for a Tuareg man is Amajagh (var. Amashegh, Amahagh), the term for a woman Tamajaq (var. Tamasheq, Tamahaq, Timajaghen).

Tuareg man with a sword

The spelling variants given reflect the variety of the Tuareg dialects, but they all reflect the same linguistic root. Some Tuaregs preferred to be called Limajgn or Temasheq; and were akin to Amazigh, meaning free men, they became a hybrid by combining in their blood with several races such as Targi, Arabic and Africans, due to the living with the Arabs in the north and with the black Africans in the South.

Also encountered in ethnographic literature of the early 20th century is the name Kel Tagelmust "People of the Veil" and "the Blue People" (for the indigo colour of their veils and other clothing, which sometimes stains the skin underneath.

Tuareg men "the blue people"

Tuareg Tribes (Cole)

Tuaregs word "Cole" which means "the people," is used for the identification of their tribal branches. there are major tribal confederations divided geographically into two main groups, namely:

(1)Tuareg tribes in desert of southern Algeria and the Fezzan in Libya has the most important tribes and they are as follows:

*Cole Hgar and Cole Aaajer in the desert of Algeria,

*Limngazn ,Oragen and Cole Aaajer in Fezzan and the city of Ghadames in Libya at the confluence of the borders with Tunisia and Algeria.

(2)Tuareg tribes of the coast, including:

*Cole Ayer and Cole Lmadn in Niger.

*Cole Litram, Cole Adraaar, Cole Tdmokt , Cole Ansar ( El Ansar), and Cole Alsswoq (traders) and the other in the Republic of Mali.

Tuareg kids

Language

The Tuareg speak a Berber language known as Tamajaq (also called Tamasheq or Tamahaq, according to the region where it is spoken), which appears to have several dialects spoken in different regions (Greenberg, 1970). The language is called Tamasheq by western Tuareg in Mali, Tamahaq among Algerian and Libyan Tuareg, and Tamajaq in the Azawagh and Aïr regions, Niger.

Tuareg woman from Timbuctu, Mali

The Tuareg distinguished themselves from other Berbers during their ancient times in Amazigh by preserving the dialect of Tamazight "Hackler" and they write their letters "Tifinagh" from right to left and from top to bottom and vice versa. Tifinagh (also called Shifinagh and Tifinar) is Tuareg Tamajaq writing system. The origins of "Tifinagh" remain unclear. An old version of Tifinagh, also known as Libyco-Berber, dates to between the 3rd century BC and the 3rd century AD in northwestern Africa (Gaudio, 1993).

Ancient Touareg Tifinagh script (tablet)

The Tuareg’s Tifinagh alphabet is composed of simple geometrical signs, it contains 21 to 27 signs, and are used according to the region. The Tifinagh language is written by tradition on stones, trunks and in the sand and is very difficult to read. French missionary Charles de Foucauld famously compiled a dictionary of the Tuareg language.

Nowadays one can see the Tifinagh’s letters still in the mountains and caves, an archeological evidence to the existence of the Tuareg in the desert since ancient times. According to some sources, the Berber dialect they speak is already one of the ancient Arabic dialects.

Though they think of themselves as a big unity the Tuareg are divided into several tribes and clans. Symbolizing their identity they call themselves "Cole Tmashek“, the people who speaks Tamashek.

Tuareg woman

History

The origin of Tuaregs who had gain the character of «Lords of desert» due to their persistent ability to confront and challenge the circumstances of geography and harsh climate is shrouded in mystery. No one knows the true origin of the Tuareg, where they came from or when they arrived in the Sahara. There are many schools of thought about the origins of the Tuareg.

Touareg people of Mali.

Historically, the Tuareg were recorded by the Greek historian Herodotus in the 5th Century BC in his travelogue during his travels to ancient Egypt and some parts of North Africa.

Ibn Battuta in his writings about his famous trips in Africa had this to say about the Tuareg: "They are Morabiteen state assets, and generally belong to the majority of the Touareg tribes Sanhaja.” Ibn Khaldun called the Tuareg masked people and like all Arab historians he classified them in the second layer of the "Sanhaja" In his words there are of many areas including "Kazolah", "Lamtonah", "Misratah" , "Laamtah" and "Rikah ". Some historians also aver that Tuaregs are people of Berbers extraction who appeared in North Africa and were one of the tribes of prehistoric races.

Frenchman Gustave Le Bon makes an interesting observation that the black hair Tuaregs were Berbers who migrated from the shores of the Euphrates and north of the countries inhabited by the Arabs, whilst the blond hair and blue eyes Tuaregs migrated from as far as Europe and were of Caucasoid blood. He postulated that the evidence could be found by comparing the stone monuments in Africa and the stone monuments discovered in northern Europe that shows same rock art of Tuaregs (Abual-Qasim Muhammad Crowe. Abdullah shareat. Dar Maghreb -Tunisia, p.12).

Tuareg girls

Abdul Qadir Jami Ferry said the word 'Touareg" is collection of the word Altargi, which is the name that the Arabs called the proportion of the Berber tribes living in the desert (Targa areas) of the ocean (Atlantic) close to Ghadames (Arabs Touareg of the Sahara, Akoshat Mohammed Said. Centre for Study and Research on the Sahara, 1989, p.27).

Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, right, meets Touareg men in Ain Salah,Algeria

From their Oral history, when one ask a Tuareg about their origin, they often assert that they originated from the Hamiriya in Yemen. From there they came to settle at Tafilalt and expanded southward from the Tafilalt region into the Sahel under their legendary queen Tin Hinan, who is assumed to have lived in the 4th or 5th century. Tin Hinan is credited in Tuareg lore with uniting the ancestral tribes and founding the unique culture that continues to the present day. At Abalessa, a grave traditionally held to be hers has been scientifically studied.

Tin Hinan Queen of Hoggar (today South Algeria)

However, the authentic information about the Tuareg origin is the consensus by historians who assert that Tuaregs descended from the Amazigh branch of Berber ancestors who lived in North Africa some centuries ago. This assertion that Tuaregs are of North African origin is supported by recent genetics studies into Tuareg`s Y-Chrosome DNA (Y chromosomes and mtDNA of Tuareg nomads from the African Sahel) and was published in European Journal of Human Genetics (2010). The studies found out that E1b1b1b (E-M81), the major haplogroup in Tuaregs, is the most common Y chromosome haplogroup in North Africa, dominated by its sub-clade E-M183. It is thought to have originated in North Africa 5,600 years ago.

The parent clade E1b1b originated in East Africa. Colloquially referred to as the Berber marker for its prevalence among Mozabite, Middle Atlas, Kabyle people and other Berber groups, E-M81 is also predominant among other North African groups. It reaches frequencies of up to 100 percent in some parts of the Maghreb.

Tuareg refugee camp in Burkina Faso

Y-Dna haplogroups, passed on exclusively through the paternal line, were found at the following frequencies in Tuaregs:

| Population | Nb | A/B | E1b1a | E-M35 | E-M78 | E-M81 | E-M123 | F | K-M9 | G | I | J1 | J2 | R1a | R1b | Other | Study |

| 1 Tuaregs from Libya | 47 | 0 | 42.5% | 0 | 0 | 48.9% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.4% | 2.1% | Ottoni et al. (2011) |

| 2 Tuaregs from Mali | 11 | 0 | 9.1% | 0 | 9.1% | 81.8% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Pereira et al. (2011) |

| 3 Tuaregs from Burkina Faso | 18 | 0 | 16.7% | 0 | 0 | 77.8% | 0 | 0 | 5.6% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Pereira et al. (2011) |

| 4 Tuaregs from Niger | 18 | 5.6% | 44.4% | 0 | 5.6% | 11.1% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33.3% | 0 | Pereira et al. (2011) |

Overall, a cline appears, with Algerian Tuaregs being closer to other Berbers and Arabs, and those from southern Mali being more similar to Sub-Saharan Africans, see also: Deep into the roots of the Libyan Tuareg: a genetic survey of their paternal heritage

Tuareg girl

So as it stands, prior to around 1200 B.C., the North African ancestors of the Tuareg lived on the northern fringes of the Sahara, like most other Berber populations - but the introduction of the horse into North Africa in the mid-second millennium B.C. (and then the camel in the first century B.C.) enabled them to expand southwards across the desert. In medieval and early modern times, they established a succession of powerful desert federations which clashed with each other and with black-African states on the southern fringes of the Sahara.

By the 10th century A.D., the Tuareg had helped introduce Islam to West Africa, while economically they prospered from their control of the trans-Saharan gold, salt and slave trades. Indeed, Tuareg slave-raiding made them widely feared among sub-Saharan Africans.

But, just as the Tuareg had their powerful political structures and identities, so did the black-African population of southern Mali, who established the medieval Songhai and Mali empires - the latter name being resurrected as the name of the modern state.

Tuareg from Algeria

Tuareg territory covered (and still covers) not only northern Mali, but western Niger, southern Algeria and southwest Libya. And yet - like the Kurds and the Lapps and many other peoples - their land is divided between internationally recognized modern nation states.

The "partition" of the Tuaregs' desert land was carried out by the French in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Their vast territory merely formed the peripheral desert hinterlands of French coastal or riverine colonies in North and West Africa. The French colonial authorities thought that the desert was economically worthless.

The Tuareg territory was organised into confederations, each ruled by a supreme Chief (Amenokal), along with a counsel of elders from each tribe. These confederations are sometimes called "Drum Groups" after the Amenokal's symbol of authority, a drum. Clan (Tewsit) elders, called Imegharan (wisemen), are chosen to assist the chief of the confederation. Historically, there are seven recent major confederations:

Kel Ajjer or Azjar: centre is the oasis of Aghat (Ghat).

Kel Ahaggar, in Ahaggar mountains.

Kel Adagh, or Kel Assuk: Kidal, and Tin Buktu

Iwillimmidan Kel Ataram, or Western Iwillimmidan: Ménaka, and Azawagh region (Mali)

Iwillimmidan Kel Denneg, or Eastern Iwillimmidan: Tchin-Tabaraden, Abalagh, Teliya Azawagh (Niger).

Kel Ayr: Assodé, Agadez, In Gal, Timia and Ifrwan.

Kel Gres: Zinder and Tanut (Tanout) and south into northern Nigeria.

Kel Owey: Aïr Massif, seasonally south to Tessaoua (Niger)

In the late 19th century, the Tuareg resisted the French colonial invasion of their Central Saharan homelands. Tuareg broadswords were no match for the more advanced weapons of French troops. After numerous massacres on both sides, the Tuareg were subdued and required to sign treaties in Mali 1905 and Niger 1917. In southern Morocco and Algeria, the French met some of the strongest resistance from the Ahaggar Tuareg. Their Amenokal, traditional chief Moussa ag Amastan, fought numerous battles in defence of the region. Finally, Tuareg territories were taken under French governance, and their confederations were largely dismantled and reorganised

As a result, two totally different governmental traditions developed in Mali - one in the more agricultural (black-African) south and another in the less valued desert (Tuareg) north. When African countries achieved widespread independence in the 1960s, the traditional Tuareg territory was divided among a number of modern nations: Niger, Mali, Algeria, Libya, and Burkina Faso. Competition for resources in the Sahel has since led to conflicts between the Tuareg and neighboring African groups, especially after political disruption following French colonization and independence. There have been tight restrictions placed on nomadization because of high population growth. Desertification is exacerbated by human activity i.e.; exploitation of resources and the increased firewood needs of growing cities. Some Tuareg are therefore experimenting with farming; some have been forced to abandon herding and seek jobs in towns and cities.

![]()

In Mali, a Tuareg uprising resurfaced in the Adrar N'Fughas mountains in the 1960s, following Mali's independence. Several Tuareg joined, including some from the Adrar des Iforas in northeastern Mali. The 1960s' rebellion was a fight between a group of Tuareg and the newly independent state of Mali. The Malian Army suppressed the revolt. Resentment among the Tuareg fueled the second uprising.

This second (or third) uprising was in May 1990. At this time, in the aftermath of a clash between government soldiers and Tuareg outside a prison in Tchin-Tabaraden, Niger, Tuareg in both Mali and Niger claimed autonomy for their traditional homeland: (Ténéré, capital Agadez, in Niger and the Azawad and Kidal regions of Mali). Deadly clashes between Tuareg fighters (with leaders such as Mano Dayak) and the military of both countries followed, with deaths numbering well into the thousands. Negotiations initiated by France and Algeria led to peace agreements (January 11, 1992 in Mali and 1995 in Niger). Both agreements called for decentralization of national power and guaranteed the integration of Tuareg resistance fighters into the countries' respective national armies.

Major fighting between the Tuareg resistance and government security forces ended after the 1995 and 1996 agreements. As of 2004, sporadic fighting continued in Niger between government forces and Tuareg groups struggling for independence. In 2007, a new surge in violence occurred.

Since the development of Berberism in North Africa in the 1990s, there has also been a Tuareg ethnic revival.

Since 1998, three different flags have been designed to represent the Tuareg. In Niger, the Tuareg people remain diplomatically and economically marginalized, remaining poor and not being represented in Niger's central government

Tuareg woman

Economy

Subsistance and Commercial Activities.

The Tuareg are a pastoral people, having an economy based on livestock breeding, trading, and agriculture.

Traditionally, occupations corresponded to social-stratum affiliation, determined by descent. Tuareg are distinguished in their native language as the Imouhar, meaning the free people. Nobles controlled the caravan trade, owned most camels, and remained more nomadic, coming into oases only to collect a proportion of the harvest from their client and servile peoples.

Here are different types of caravans:

caravans transporting food: dates, millet, dried meat, dried Tuareg cheese, butter etc.

caravans transporting garments, alasho indigo turbans, leather products, ostrich feathers,

caravans transporting salt: salt caravans used for exchange against other products.

caravans transporting nothing but made to sell and buy camels.

Oasis In The Libyan Desert

Salt mines or salines in the desert.

Tin Garaban near Ghat in Azjar, Libya.

Amadghor in Ahaggar, Algeria.

Todennit in Tanezruft desert, Mali.

Tagidda N Tesemt in Azawagh, Niger

Fashi in Ténéré desert, Niger

Bilma in Kawar, Niger

Tributary groups raided and traded for nobles and also herded smaller livestock, such as goats, in usufruct relationships with nobles. Peoples of varying degrees of client and servile status performed domestic and herding labor for nobles. Smiths manufactured jewelry and household tools and performed praise songs for noble patron families, serving as important oral historians and political intermediaries. Owing to natural disasters and political tensions, it is now increasingly difficult to make a living solely from nomadic stockbreeding.

Thus, social stratum, occupation, and socioeconomic status tend to be less coincident. Most rural Tareg today combine subsistence methods, practicing herding, oasis gardening, caravan trading, and migrant labor. Nomadic stockbreeding still confers great prestige, however, and gardening remains stigmatized as a servile occupation. Other careers being pursued in the late twentieth century include creating art for tourists, at which smiths are particularly active, as artisans in towns, and guarding houses, also in the towns. On oases, crops include millet, barley, wheat, maize, onions, tomatoes, and dates.

A contemporary variant is occurring in northern Niger, in a traditionally Tuareg territory that comprises most of the uranium-rich land of the country. The central government in Niamey has shown itself unwilling to cede control of the highly profitable mining to indigenous clans. The Tuareg are determined not to relinquish the prospect of substantial economic benefit. The French government has independently tried to defend a French firm, Areva, established in Niger for fifty years and now mining the massive Imouraren deposit.

Additional complaints against Areva are that it is: "...plundering...the natural resources and [draining] the fossil deposits. It is undoubtedly an ecological catastrophe". These mines yield uranium ores, which are then processed to produce yellowcake, crucial to the nuclear power industry (as well as aspirational nuclear powers). In 2007, some Tuareg people in Niger allied themselves with the Niger Movement for Justice (MNJ), a rebel group operating in the north of the country. During 2004–2007, U.S. Special Forces teams trained Tuareg units of the Nigerien Army in the Sahel region as part of the Trans-Sahara Counter-Terrorism Partnership. Some of these trainees are reported to have fought in the 2007 rebellion within the MNJ. The goal of these Tuareg appears to be economic and political control of ancestral lands, rather than operating from religious and political ideologies.

Despite the Sahara's erratic and unpredictable rainfall patterns, the Tuareg have managed to survive in the hostile desert environment for centuries. Over recent years however, depletion of water by the uranium exploitation process combined with the effects of climate change are threatening their ability to subsist. Uranium mining has diminished and degraded Tuareg grazing lands. Not only does the mining industry produce radioactive waste that can contaminate crucial sources of ground water resulting in cancer, stillbirths, and genetic defects but it also uses up huge quantities of water in a region where water is already scarce.

This is exacerbated by the increased rate of desertification thought to be the result of global warming. Lack of water forces the Tuareg to compete with southern farming communities for scarce resources and this has led to tensions and clashes between these communities. The precise levels of environmental and social impact of the mining industry have proved difficult to monitor due to governmental obstruction.

Food

Taguella is a flat bread made from millet, a grain, which is cooked on charcoals in the sand and eaten with a heavy sauce. Millet porridge is a staple much like ugali and fufu. Millet is boiled with water to make a pap and eaten with milk or a heavy sauce.

Common dairy foods are goat's and camel's milk, as well as cheese and yogurt made from them. Eghajira is a thick beverage drunk with a ladle. It is made by pounding millet, goat cheese, dates, milk and sugar and is served on festivals like Eid ul-Fitr and Eid al-Adha. A popular tea, gunpowder tea, is poured three times in and out of a tea pot with mint and sugar into tiny glasses.

Preparation of communal meal for extended Tuareg family

Trade

The caravan trade, although today less important than formerly, persists in the region between the Air Mountains and Kano, Nigeria. Men from the Aïr spend five to seven months each year on camel caravans, traveling to Bilma for dates and salt, and then to Kano to trade them for millet and other foodstuffs, household tools, and luxury items such as spices, perfume, and cloth.

Division of Labor

Most camel herding is still done by men; although women may inherit and own camels, they tend to own and herd more goats, sheep, and donkeys. Caravan trade is exclusively conducted by men. A woman may, however, indirectly participate in the caravan trade by sending her camels with a male relative, who returns with goods for her. Men plant and irrigate gardens, and women harvest the crops. Whereas women may own gardens and date palms, they leave the work of tending them to male relatives.

Gender Construction